The copy from the article image is hard to read therefore it has been typed below to help visitors read the copy and view the images. Copy from Article:

By William B. Dickinson

United Press Staff Correspondent

New York, Nov. 30 (UP)- Charles A. Lindbergh shot down a Japanese Zero

plane from his P-38 over Beraab on October 10, 1944, it may be revealed

now.

This story was first given me by a high military authority more than 13 months ago, but at the time I pledged to keep it a secret until the right time came. That officer has released me from that pledge, so now it can be told.

Lindbergh, who was in the Pacific war theater as a technician, was supposed to be a non-combatant. However, he accompanied American fighter planes on a raid on oil installations at Balikpapan, Borneo, and became involved with a Japanese Zero. One short burst from his guns sent the enemy spinning down in flames.

After that Gen. George C. Kenney, commander of the far eastern air forces, ordered Lindbergh not to make any more combat missions.

I first heard this story on the cruiser Nashville while I was en route to the Leyte invasion with Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

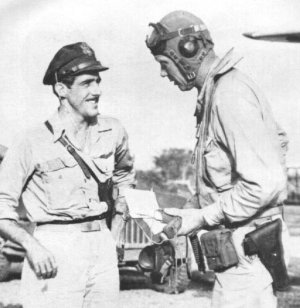

When the fight occurred, Lindbergh had been in the Pacific only a few weeks. He was there to train American fighter pilots, most of them about half his own age of 42.

The famous flier who thrilled the world with his "Lone Eagle" trans-Atlantic flight in 1927, had worked out flying method which made it possible almost doubling the range of the Lightning P-38 fighter. The importance of this in the southwest Pacific where principal Japanese targets were far distant from our bases, cannot be overestimated.

Before Lindbergh visited that theater and taught his methods, our fighters had been unable, even when equipped with auxiliary wing and belly tanks, to escort our bombers on raids of more than 400 miles from our bases.

The success of his methods which consisted mostly of conserving gasoline by throttle control, is best illustrated by the communiqué issued by MacArthur's headquarters on October 13, which gave the news of the Balikpapan raid of October 10 - except, of course, for Lindbergh's part in it.

That communiqué reported that five groups of heavy bombers - they were B-24 Liberators - had dropped 135 tons of high explosive bombs on Balikpapan. They were escorted by American fighters, which had flown a round trip of 1500 miles and had shot down most of the 36 Japanese fighters destroyed. Our losses were three fighters and one bomber.

In other words, the distance our fighters could fly to protect our bombers on their raids had been almost doubled. Kenney and other air force leaders gave Lindbergh most of the credit.

But the communiqué didn't report that Lindbergh had gone along, in his own words, "just to see who it works out."

He was flying with America's finest fighter pilots. Maj. Richard Bong of Poplar, Wis., whose score of 40 enemy planes destroyed made him this country's top-ranking ace of all time, was in the formation. Bong got his 29th and 30th that day. Maj. Thomas B. McGuire of Ridgefield, N.J., also was there. There wasn't a green pilot among the more than 30 fighters on the mission.

McGuire was to die later strafing a Jap destroyer in the Philippines, and Bong in a test flight of a jet plane in California. Both told me, in interviews before their deaths:

"Lindbergh was as hot a pilot as any of us. He would have been out there knocking off Japs every day if Kenney had let him."

There were Japanese aplenty that day at Balikpapan. At least 60 Japanese fighters met the bombers and fighters as they went into the target. And the fight lasted until the American planes were nearly an hour out of the homeward trip.

Lindbergh got his Jap fairly early in the fight. The zero roared in on an American bomber, and the famous flier dived on his tail. One short burst from close in sent the Japanese plane twisting down in flames. The enemy pilot did not parachute. Probably he had been killed by the bullets with his plane undamaged. v No more Japanese came within range of Lindbergh's guns that day. He returned with his plane undamaged.

When the day's kills were totaled, after the raid, there was a difficulty. One enemy plane couldn't be credited to any pilot, because Lindbergh's name couldn't go in the record.

"It threw our bookkeeping off a bit," a high air force officer told me, laughing. "Here we are with one more plane in our total of Japanese shot down by fighter command than the individual records show. But I guess we'll let it ride that way."